Originally published in ThreeSixty. Reprinted with permission.

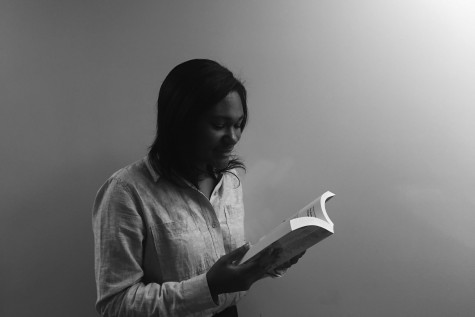

MY FRIEND AND I were walking the streets of southern France with an almost unbearable heat seeping in from all directions. We were making our way to the beach, burning up, yet still happy to have each other’s company.

A loud honk startled us, and we turned to see an orange-looking old man smiling at us in his car. He began shouting a slew of vulgar things he wanted to do to us, or rather, to our bodies.

Instinctively, I grabbed onto my friend’s arm and buried my face into her shoulder, feeling the intense sting of embarrassment.

“What do we do?” I asked her, genuinely confused.

She told me to just ignore it. Her eyes fixed forward, and her expression hardened. I couldn’t understand her response at the time. She had put on a guise reserved for these situations. However, by the time I went home, I too was learned in the ways of women.

I was 16 when I arrived in France for a year abroad, relatively young and relatively alone. My head was flushed with romantic ideas from too many movies and not enough maturity. I was still a girl.

For me, womanhood wasn’t the first time I bled between my legs. Nor was it when I was introduced to the piece of cloth that I’d tie around my chest. No, my banishment from girlhood was much more sinister.

It was, above all, my body, or more precisely, the reaction to it. My French host mother often made comments about my weight. She praised me when she found me thin, tutted if I became heavier. I was interrogated about my mom’s figure, which was her way of encouraging me to stay slender.

I wasn’t sure how to react to this scrutiny. Never before had an adult taken such an interest in my weight. There was a time in elementary school when other children had. I starved myself that summer.

I sense my classmates were forced under this humiliating inspection as well. There was hardly a time when a girl wasn’t dieting. A friend once showed me an inventory of half-naked pictures of herself in the mirror. She thought a space between her thighs determined her self-worth.

Another girl’s host mother assured her it was OK to look pretty, so she veiled herself in makeup. I, too, began fixing myself. Each day I poked my eyes with eyeliner, smeared foundation on my face and buckled in high heels. At times it felt as though I was a one-dimensional creature whose value depended on how much I could attract men.

They were at cocktail parties, their liver-spotted skin wrinkling up around their eyes as they inquired about my non-existent sex life.

“Careful, Jacques, she’s a minor!” they said.

The men were in cars, whistling and honking as I forced myself to look straight ahead. They were in the street, pestering me for a date, whispering lewd things in my ear, unwilling to take no for an answer.

I was outwardly polite as a fury ate away at my insides. This anger was double-edged: One side pointed at those who thought they were entitled to harass me. The other was turned inward – mad at myself for accepting this degradation, for wanting to scream yet smiling instead.

Nothing in the U.S. had prepared me to deal with male attention. How could I have known what to do when a charming young British man placed a hand on my knee? Or when he brushed the hair out of my face? Or when he cupped my chin in his hand to better appraise me?

I remember seeing myself in his pupils. Staring at my reflection, I thought about the large gap of time between girl and womanhood, and how quickly it had elapsed in just a few months.

I couldn’t look into his eyes for the rest of the evening.

By the end of my year in France, I no longer fell down flights of stairs while wearing heels. I applied eyeliner without blinding myself. I shaved my legs without leaving nicks. And yet it wasn’t enough.

“You’re free to wear red lipstick,” a friend said, quite casually. “Just know that everyone will think you’re a slut.”

And I flashed back to my school in America again, a classmate feverishly arguing that a girl was a whore, but “it was just different” when a boy did the same. I knew these rules existed before I left, though I never imagined they’d apply to me.

“One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman,” French feminist Simone de Beauvoir once wrote. How does one become a woman?

I know the expectations. I’ve considered them carefully, though I can’t decide whether to follow them or not.

As I write these words, I feel stuck. Stuck between whether to laugh at the absurdity of the situation or be enraged by it. Or perhaps I should cry, not only for myself but also for the women who came before me, and the girls who will come after.