Clearing up caucus confusion

Students travel to Iowa to volunteer for '16 election

February 4, 2016

A check on a ballot. Though it is commonplace for Americans to vote in the presidential election every four years, the caucuses leading up to the nomination of a Republican and a Democratic candidate has the potential to perplex.

In a poll of 40 students, nineteen considered themselves “politically engaged.” Out of those nineteen, only six could define and/or describe what a caucus is. Students who have volunteered for political parties, follow the news, and engage in political debates alike could not explain the process.

As students age into the first-time voter category, the time for civics is now.

Caucuses and primary elections serve to whittle down presidential hopefuls to one nomination for each political party. The selected Democrat and Republican, along with any independent or smaller parties’ candidates, face off in the months following the caucus in a battle for the oval office.

53 students and 8 teachers traveled to Iowa. On Saturday, they waited to see Rand Paul after his appearance on Meet the Press.

Each state decides between a caucus and a primary to facilitate this process. Minnesota employs the former technique. AP Government teacher David Graham describes the caucusing process. “The idea behind [caucuses] comes out of the sixties,” says Graham. “[It comes] out of the idea that people should have more say in their government. So, with caucuses you get everyone in your precinct and in your neighborhood and you meet by party[…] You go and you essentially hear what your neighbors are thinking.”

Furthermore, Graham delineates the difference between the two forms of internal party nominations. “A primary is just essentially go out and vote[…] It takes maybe fifteen minutes. Caucusing takes an hour at least.”

Another difference lies in the format. While primaries are easier to participate in due to the simplicity of casting a vote, caucuses allows a different type of participation. Individuals often prepare with deep research on a candidate’s policies, history, and goals to participate in debates over the merits of each presidential hopeful within a party.

The structural differences of caucusing versus primary elections also creates varying levels of involvement. Attention to detail and knowledge of parliamentary procedure–the rules and customs by which a governing meeting operates under–is what lends to an average of only 6% involvement in caucuses, according to Graham. Based on the sheer reality that it’s easier and more expedient to cast a vote than it is to discuss policies, more people usually show up in states that employ primary elections.

The Iowa Caucus is the impetus of the presidential election process. The process is governed by the Republican and Democratic parties, and each party does things in a different way. The Republican caucus’ process is like a primary; voters select candidates by a secret ballot. The Democratic process is a true caucus; Iowans gather, discuss, and then publicly state their opinion. Candidates, voters, and donors alike use the results from Iowa to determine long-term electability of potential nominees. Iowa’s chief purpose, then, is rooting out candidates least likely to be nominated. Iowa’s done a good job of it, too; no candidate who has finished worse than fourth has ever gone on to win either party nomination.

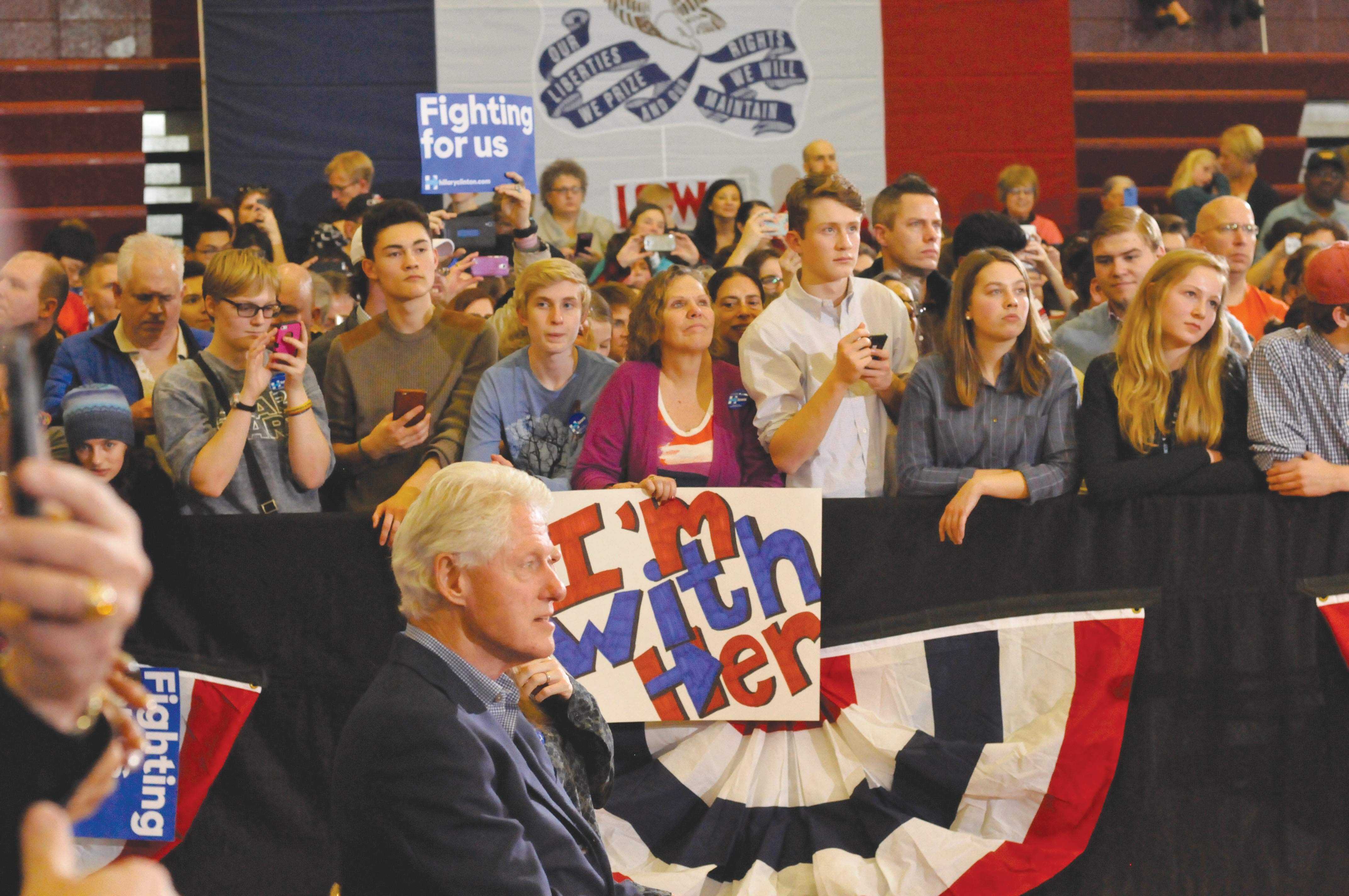

from left: Rachel Eggert ‘19, Ben Lee ‘19, Kyle Swing ‘18, Deborah Weiss, Nick Crosby ‘18, and Zoe Zellmer ‘17 are a few of the Blake community members who attended Hillary Clinton’s rally in Iowa.

Despite the confusion over the caucusing process, students are not discouraged from taking advantage of the opportunity to participate in our country’s political system. Shiv Jhanjee ‘18 stated, “I haven’t been very politically active in the past … but I’ve realized that it’s probably something I should care about, seeing as I’m a citizen of the United States.”

Annabella Walser ‘18 added to the idea of civic duty: “our generation has a lot of influence in the future of our country and I think that going there and supporting something that you believe in is good, because this is our future.”

Beyond civic engagement, caucusing serves many more purposes than just electing a party’s candidate. Minnesota’s Secretary of State’s website notes that the four purposes of caucuses are to elect community organizers within each precinct, brainstorm party platforms, support a candidate, and select precinct representatives to vouch for selected candidates and policies at future political conventions.

“You have to elect delegates from your precinct, and say you can only elect three delegates and thirty people show up, then a lot of the caucus is figuring out who will go and represent.” This means that often “the people that go tend to be the most dedicated, the most extreme,” says Graham.

With anti-establishment candidates such as Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders commanding high numbers in recent polls, students wondered whether the caucusing process favored candidates with extreme views. Since these politicians tend to have the most passionate supporters, their supporters are most likely to vote; moderate voters, on the other hand, may stay home and wait until the general election in November to show their support.

Maddie McConkey ‘16 explained, “your caucus is only your Democratic caucus or your Republican caucus, so only self-declared Republicans who really care about Republican politics are going to show up to the Republican caucus … it’s not an accurate representation of the general population.” With the questionable accuracy of the caucusing process, would it be worthwhile to switch to a simpler system that encourages higher rates of participation?

Even with confusion over the caucusing process, some students favored the amount of thought required for caucuses in relation to primaries. McConkey lauded caucuses, stating, “In the primary you’re not going off any research or anything necessarily. You could just watch a TV commercial and then go in and primary and vote for that person, whereas in a caucus you actually have to engage in a discussion about that person’s policies.”

In terms of attending the Minnesota Caucus, anyone can show up, but only those who will be eligible to vote in the November election can participate. Sean Bazzett ‘18, although unable to participate due to his age, attended a caucus and remembers the process clearly: “you could second things, you could put your name on resolutions.” In other words, caucus attendees often endorse others’ ideas and sign off on written suggestions of how to address issues.

Bazzett also recalls the relatively small turnout: “my parents really wished that more people would have came because it was sort of like whoever had the most people really had the most power.”

from left: Darrel Hong ’16, Julia Shepard ’16, Robyn Lipschultz ’16, Bennett Mattson ’17, Caitlin Kearney ’16, Sam Gittleman ’16, and Calvin Rusley ’16 all show their support at Hillary Clinton’s rally with her slogan “Fighting for us.”

The Iowa Caucus takes place on February 1. In the words of former Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, “As a citizen, you need to know how to be a part of it, how to express yourself – and not just by voting.” Though it may seem confusing, it is your responsibility to stay involved and informed in the Iowa Caucus.

In Minnesota, political pundits and servants to civic duty will be called into their neighborhood on March 1st, 2016. Those who will be eighteen before November 8th, 2016 are welcome to participate. Those who will not be of voting age in time are still welcome to attend and engage in the political process.

Timing and location for each party is determined by individual precincts closer to the date. To find out which precinct you’re in, as well as important information about your local and state representatives, visit http://www.gis.leg.mn/OpenLayers/precincts/.