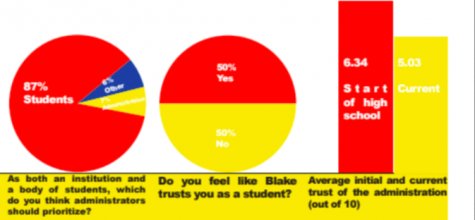

An anonymous survey conducted by The Spectrum of 180 students from all four grades found that 50% of Upper School students believe that Blake administrators do not trust them.

Although it is often painted in broad strokes, high level administrators, for the purpose of this survey, consist of the Head of School, Associate Head of School, Upper School Director, Assistant Upper School Director, and other directors of programs, such as the Director of Security and the Director of Buildings and Grounds. The survey focused on these individuals and excluded deans from consideration.

The survey demonstrated rifts between students and administrators. Administrators are in charge of operations, and have a number of factors to consider when interacting with students. The realities of their jobs make it hard to be transparent, personable, and congenial when dealing with serious matters. Upper School Assistant Director Paul Menge explains that, “Sometimes people don’t have all of the information, and sometimes they can’t…there are some things that you want to be confidential for good reason to protect people’s privacy.” But to many students zwho don’t always consider the need for balance differing needs of both students and the institution, this split of focus can often come off as distrusting.

“The only time we’ve come in contact with administrators is when we are in trouble, or we have done something bad, so I feel like the only viewpoint we have of them is them being punishers or they just give us bad consequences,” explains Eesha Nagwani ‘19 as she reflects on her experience with administrators, “I see the administration as something to be fearful of.”

In the same survey, The Spectrum found that the average trust rating of a freshman in administrators is 6.71 out of 10. In contrast, the average trust rating of a senior is 3.79 on the same scale.

As students progress into senior year, age old traditions such as the senior skip day, the freedom that comes with the senior speech, and the senior prank cause friction between students and administrators. And as students age, confidence to question decisions and authority becomes more widespread.

Peer pressure to join a bandwagon of resistance to administrative policies is also prevalent, perhaps obscuring opinions that sway more positively. Sonia Baig ‘21 explains that “People might have positive opinions of the administration but might not want to share them because of social pressures to have a negative opinion about them, so I think it’s hard to know what students really think.”

However, more experience in the upper school allows students more interactions with the administration, allowing students to gain firsthand opinions of policies that they may not have had to personally deal with previously. Sarah Yousha ‘20 explains that, “As I’ve had more experience with going to [administrators] and trying to get things done, it has been very inconsistent and a lot of it is more protecting Blake rather than protecting the students.” Baig, a Forum representative for the Class of 2021, agrees, explaining how issues already pre-decided by the administration may come to Forum: “So sometimes they want to communicate those things to us, but it’s not necessarily for the purpose of getting our opinions to change those things, but rather for the checkmark of hearing us out.”

Frequently, administrators are hesitant about being quoted in The Spectrum, often wishing to change their language within quotes. Reputation seems to be a tangible fear in the mind of administrators, which is in contrast to The Blake School’s core value of respect, where all members possess “an openness to that which is different,” interactions such as these only leave a negative impression on students, painting administrators as reputation-oriented rather than grounded in discussion, however difficult it may be. The lack of allegiance to the well-publicized values of the school only stunt trust in administrators, as it appears they are concerned only with damage control.

Paris Del Castillo ‘19 explains, “In this school, everyone has to make you trust them. You aren’t trusted initially, you have to gain it. For anyone in the administration, you have to have a personal connection to them to make them trust you.”

This innate nature of suspicion towards the students is present in many activities. The communication of the new security measures requiring badging in upon entry and exit, as well as the indefinite closure of the east door to all students, the implementation of automatic breathalyzing at dances, censorship of senior chants, and general controlling overview of all student activities, inside or outside the classroom, all communicate to the students that they are assumed guilty of recklessness and bad judgement. Anonymous short answer responses in the survey pointed to the new security policies, the email sent to parents recommending actions to take surrounding their child’s prom experience, and censorship of senior chants and other spirited activities by administrators as places of contention where they felt as if guilt was being projected upon them. Cole Mathews ‘20 explains that the email seemed to be “trying to expand their authority further than just school, or what they should have.”

Yet, most administrative measures are done with the intention to aid. A prom letter is sent out every year and was specifically asked for by parents seeking guidance. Upper School Director Joe Ruggiero explains, “I understand how some people might interpret it as though ‘we don’t trust your kids, so make sure that they are not doing the wrong thing.’ I think that’s the risk that we run in trying to partner with parents and make sure that people are accounted for.”

The perception of premature judgement due to overly aggressive communication leads to students’ resentment of administrators and administrative policies. Nagwani explains, “I don’t think they realize that we get that they don’t trust us, but then we aren’t really going to trust [them] back.”

With communication at the heart of these discrepancies in trust, increased transparency and intentional dialogue between students and administrators is key. Yousha explains, that “for students, if they don’t see results… it feels like the administration has given up, or just doesn’t want to address those concerns.”

Ruggiero acknowledges this disconnect, explaining, “I do think that at times we could do a better job of letting you know that it’s being handled. Even if it’s just, ‘ [I] can’t give you details, but know that I haven’t forgotten about it.’ We can definitely work on that.”

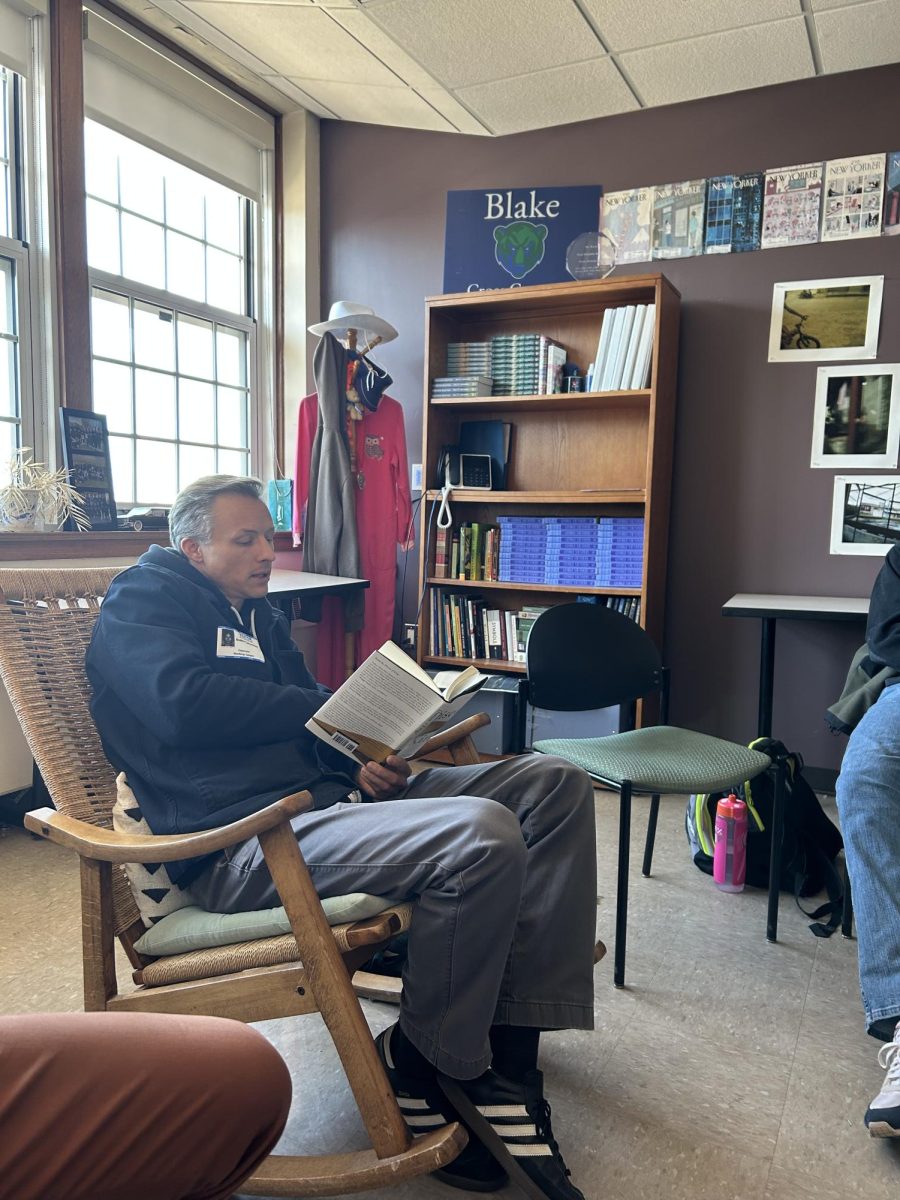

Menge feels similarly, saying that “Students having trust in their teachers and their administrators, and vice versa, is tantamount to having a healthy community….If students feel like they don’t understand why something happened, I would encourage them to seek out someone to talk about it. The strength of this school is that we are small, and that we have a lot of administrators around… all of us are willing to talk with students with questions. If somebody has a question about something, I would feel really bad if they didn’t just come and talk about it and instead made an assumption.”

In response to present trust issues and past actions, the only way forward is through the shared understanding of a common goal. Both students and administrators work constantly to create “a diverse and supportive community,” as the Mission Statement says. Ruggiero explains that in the end, “the institution is for the students. Everything we do is in the frame of mind of trying to make the student experience better, safer, and more enjoyable. We don’t always succeed in terms of how it’s perceived or taken, but that’s always the goal.”