COVID-19 changed a lot regarding school. Two years later, schools across the country have begun to revert back to pre-COVID habits in addition to creating new ones. As a whole, inflated grading practices perpetrated by teachers during the pandemic are ending, impacting studentsí workload and transcripts.

Social studies teacher Mackenzie McIlmail explains, “What we were told [by the administration] is that we could start to return to pre-COVID expectations in terms of workload and in terms of rigor.”

Throughout COVID, teachers relaxed rigor. Audrey Anderson ’23 noted, “I think sophomore year [2020-2021], there was definitely an inflation in grades.” Part of this switch was in an effort to create a more equitable learning environment for students; McIlmail furthers, “We want[ed] to be empathetic and respond to [mental health issues due to COVID] by being more flexible with due dates and expectations.” For her, this looked like assigning less complicated reading, ìSustaining your attention for a longer reading, that I think got a lot harder for students. During the pandemic, I was trying to assign less and less and less reading, like what is the bare minimum I can get through with and students still be successful. Now, I’m not as concerned about that, I hope they’re ready to return to more rigorous reading levels.”

Students’ response to increased expectations has been so far fairly positive. McIlmail notes, “I think [students] have started to meet our higher expectations, but it’s a process. We are slowly increasing rigor and expectations; at least in my class, we aren’t doing it all at once. I see students meeting the mark, but it’s still challenging, and I think that some of our students aren’t used to the level of expectation being this high compared to the last two years.”

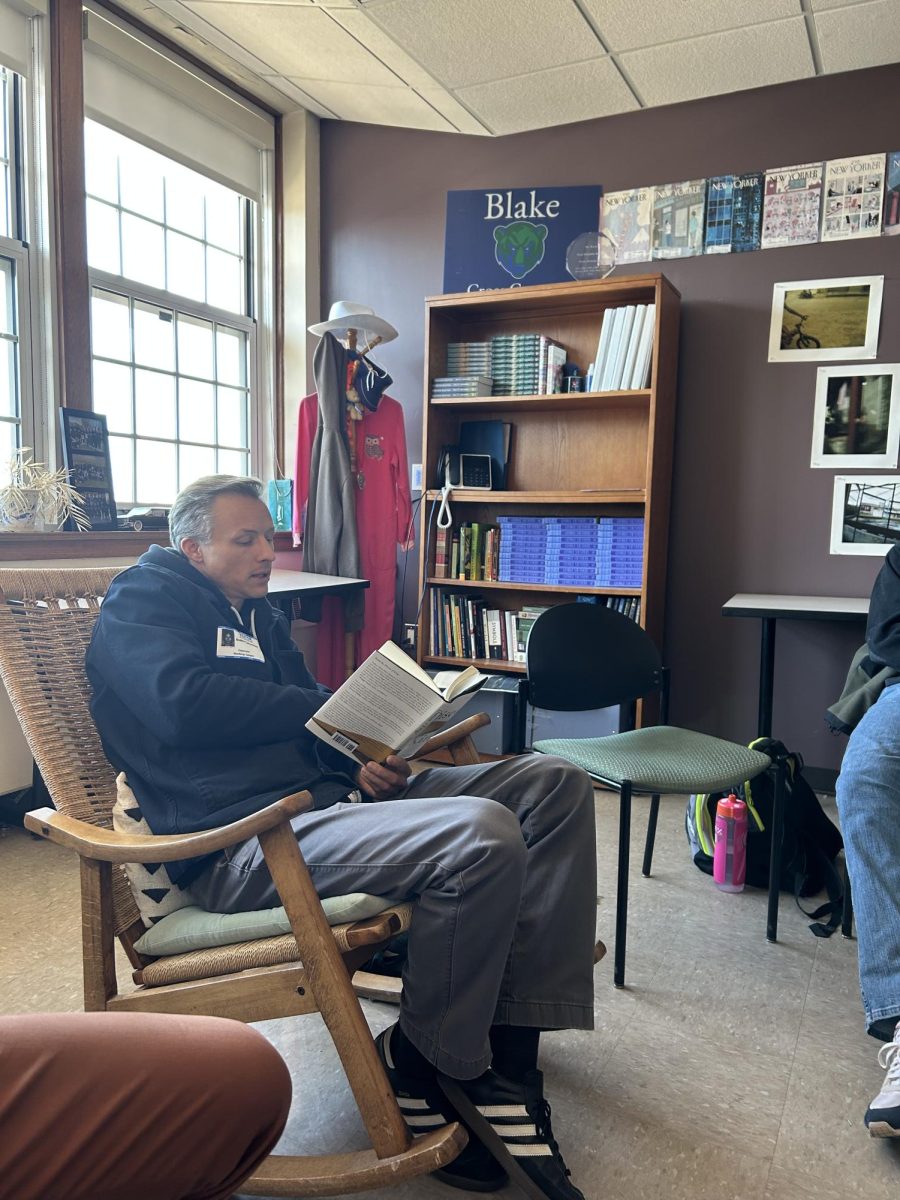

However, overall trends before, during, and after the pandemic have remained relatively the same, Cory Tao explains, “Students who value learning are always going to put in a certain amount of effort, and the students who maybe don’t connect with the content or the type of class it is, they’re not going to maybe invest as much.”

Regardless of this supposed step up in grading, efforts for equal and fair grading didn’t end with COVID. Tao explains, “If students are doing this formative work and practicing, you did it. Okay, good. Here’s some feedback. So that will then skew the final outcome in a way that might look like an inflated grade. But is it [inflated], or is it more fair?” Anderson finds grade-based accommodations fair, noting that her teachers are “still pretty generous in grading.” For example, following a challenging Physics test, “my teacher had us write up a lab and thatís going to go into the test category, and those typically do boost your grade a little bit.”

Adding to this conversation of what is fair when it comes to grading, McIlmail says, “I think equity is really important, we’re all coming from different backgrounds and different study environments at home.” Grading as a whole is inherently subjective and begs the question of how to grade in a college prep school. Tao agrees, “Technology is changing, school is changing… what would we do if we radically re-imagined a school day or a classroom?”